Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

The strategic dimension of the humanitarian-development gap – conceptual claims and empirical evidence

The 2016 United Nations World Humanitarian Summit, which took place in Istanbul/Turkey, reached an agreement to better link humanitarian assistance and development co-operation. However, this agreement leaves open the question how that can best be done in practice.

In this context, the German Institute for Development Evaluation (DEval) and the Swedish Expert Group for Aid Studies (EBA) have jointly published a structured literature review on the humanitarian-development nexus in order to explore effective linkages of international humanitarian and development responses to forced migration crises.

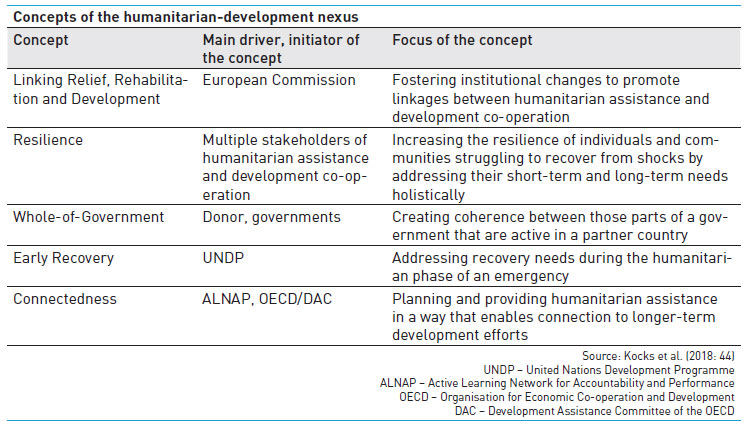

The study analyses how different concepts of the nexus debate (for an overview of these concepts, see Table on page 36) characterise the humanitarian-development gap and filters out recommendations on how to overcome this gap. The analysis reveals that the gap is a multi-dimensional phenomenon that consists of seven different sub-gaps: vision and strategy gap, planning gap, funding gap, institutional gap, ownership gap, geographic gap, and sequencing gap. Hereafter, we focus on the vision and strategy sub-gap as one of the dimensions most prominently discussed in the literature. We do so by contrasting the recommendations on how to close the vision and strategy gap with empirical evidence derived from evaluative studies on the international response to the crisis in Syria and its neighbouring countries.

The vision and strategy gap

We define the vision and strategy gap as follows:

The vision and strategy gap exists where no common strategic framework is in place among actors responding to a particular crisis, and where little or no progress is made towards integrating and aligning humanitarian and development responses based on a common vision and strategy aimed at delivering collective outcomes.

Overcoming silos – five recommendations

Humanitarian and development approaches to crisis management tend to stay in their traditional silos when joint strategic frameworks are in short supply. This undermines the ability to address underlying causes of vulnerability. Consequently, actors become less able to enhance resilience among affected people and institutions. Recommendations derived from the conceptual literature on how to bridge the vision and strategy gap are:

Recommendation 1: Working principles of humanitarian assistance and development co-operation should be balanced.

A good balance between working principles is necessary in order to improve linkages. Humanitarian assistance and development co-operation adhere to different working principles. Humanitarian assistance adheres to fundamental humanitarian principles: humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence. On the other hand, principles for effective development co-operation strongly reflect a requirement to work with and through partner governments to achieve objectives such as ownership, alignment, harmonisation, managing for results, and mutual accountability.

These different working principles may prevent linkages between the two forms of assistance, since collaboration with ‘the other side’ could signify a neglect of one’s own principles. In what form balancing is viable depends highly on external circumstances that may vary over time.

Empirical evidence

Studies of aid responses to the Syria crisis mostly focus on humanitarian actors inside Syria who are compromising on humanitarian principles to be able to provide at least some help. One controversial topic is whether attempts to keep a balance between humanitarian and development principles have positive or negative effects. In Jordan, for example, the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has a strong bilateral relationship with the government. While this relationship – in accordance with development principles of ownership and partnership – has long been considered a precondition for creating longer-term perspectives for Syrian refugees, it has also become a bone of contention. Concerns were raised regarding UNHCR's mandate and core principles such as impartiality amidst growing difficulties to protect refugees in Jordan, and due to risks of a Jordanian-Syrian border closure to minimise the influx of refugees.

Recommendation 2: Humanitarian and development actors should commit themselves to common goals to increase the coherence of interventions.

Bridging humanitarian and development responses by committing to collective outcomes – such as resilience or Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – can be an important step towards closing the gap. Once this has been achieved, humanitarian assistance and development co-operation actors can no longer act in isolation but serve as building blocks of a unified approach that makes the overall response more effective.

Empirical evidence

Strengthening resilience has emerged as the overarching goal in the Syria crisis. Political actors from both the humanitarian realm and the development realm are committed to resilience under the scope of the Regional Refugee and Resilience Plans (3RP, see Box). Nevertheless, the 3RPs distinguish between two elements – a refugee protection and humanitarian assistance component on the one hand, and a resilience and stabilisation component focusing on host communities on the other. Refugees seem to remain in the compartment of short-term relief (such as covering shelter, health and nutrition, and protection needs), while host communities benefit from longer-term measures (such as capacity building of institutions to cope with and recover from the crisis).

Regional Refugee and Resilience Plans

The Regional Refugee and Resilience Plans (3RPs) epitomise international actors’ commitment to building bridges between humanitarian assistance and development co-operation in the Middle East. They underline the necessity of profound changes when dealing with humanitarian crises, particularly in Syria. When this crisis started in 2011, the regional response with regards to refugees was initially a UN-led process of setting up National Response Plans for Syrian refugees in all neighbouring countries plus Egypt. In 2012, these plans were for the first time merged under a single umbrella – a Regional Response Plan (RRP).

The humanitarian approach to refugees was still separated from the realm of development co-operation. Two co-ordinators worked in each neighbouring country of Syria (the Humanitarian Coordinator of United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and the Resident Coordinator, usually from UNDP if present). The crisis required complex co-ordination. Disputes evolved on the mandate of some UN organisations. Consequently, co-ordination among Syria’s neighbours was merged in 2014. A Joint Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator in Jordan, Lebanon and Iraq was appointed. Calls for the inclusion of a resilience component – catering for host communities and for refugees – were becoming louder inside the UN.

Exponentially growing refugee numbers from 2013 to 2015, and the subsequent strain on host countries, made it imperative to find national and local solutions. The Jordanian Government developed a National Resilience Plan for 2014 to 2016, complementing the original National Response Plan and focusing specifically on crisis management in Jordan and its host communities. Efforts to merge the two sides led up to National Response Plans, which included a humanitarian component for refugees and a resilience component for host countries. This was also reflected at a regional level.

The first 3RP was made public in 2015 by UNHCR, highlighting longer-term commitments and objectives in neighbouring countries. The formal lead of National Response Plans belongs to nation states, though. These National Response Plans are only later fed into a Regional Plan. The emphasis on host communities, rather than on refugees, in today’s 3RPs is based on strong individual national interests among Syria’s neighbours, and on reconsidered UN policies to some extent. Resilience includes all kinds of stakeholders (from beneficiaries of humanitarian assistance to institutions in host countries), but the peculiar entry point to the Syria crisis led to a focus on host countries.

Source: Kocks et al. (2018:67)

Recommendation 3: Humanitarian and development actors should develop joint country strategies.

Donors formulating a joint crisis response strategy that integrates and aligns their humanitarian and development efforts are more likely to bridge the divide between humanitarian and development silos. Ideally, such a strategy provides guidance on how to integrate, sequence and complement humanitarian and development programmes. It ensures that both forms of assistance mutually support one another for the benefit of achieving a common outcome.

Empirical evidence

In the context of the Syria crisis, the 3RP is referred to as an important milestone in incorporating the two forms of assistance. It promotes an integrated humanitarian and development approach for scaling up resilience and formulates clear strategic objectives and indicators accompanied by sector plans – all in order to put the resilience agenda into practice. However, some donor countries have criticised the 3RP “as a wish list and not a strategy”; and the joint strategy-building efforts underlying the 3RP allegedly did not sufficiently include NGOs.

Recommendation 4: Donors should seek to align their country strategies with host countries’ strategies.

There is widespread conviction that ownership of host countries’ governments and of subnational actors is a prerequisite for effective crisis response strategies. Emphasising ownership moves the focus away from a supply-driven perspective (linkage between international humanitarian and development aid providers) and towards a more outcome-oriented approach (how to reach longer-term targets through short-term interventions).

Empirical evidence

With regard to the Syria crisis, there is evidence of strong ownership of refugee-hosting countries, which generates substantial coherence between the 3RP and national plans. However, the case of Lebanon shows that alignment becomes almost impossible if a national government has policies in place that contravene donors’ mandates and principles. In Lebanon, the Minister of Interior announced that refugees returning to Syria (after June 2014) would be stripped of their refugee status if they returned to Lebanon once again. Such a statement contradicts most donor policies of free movement for refugees, and makes alignment difficult.

Recommendation 5: Humanitarian and development responses should both be committed to longer-term engagement in protracted crises.

Response strategies are bound to fail if not supported by donors’ political will for longer-term engagement in a crisis at hand. Since protracted crises, by definition, are stretched out in time, humanitarian-development responses also require time. Only actors willing to stay enduringly are able to achieve long-term effects, especially in such crises.

Empirical evidence

After the early years of the Syria crisis response, which was more or less restricted to humanitarian aid, there is today a growing recognition that the crisis cannot be managed without longer-term development responses. This is exemplified by the 'Grand Bargain' signed by more than 30 donors, multilateral agencies and NGOs at the World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul as well as the 'UN’s Commitment to Action' (also launched at the summit), and especially new 'compact agreements' (such as those in Jordan and Lebanon). However, there are doubts about the credibility of donors' lasting engagement in the Syria crisis, as the signed commitments have not been transferred into adequate levels of funding. In addition, there is evidence that host countries abstain from developing longer-term perspectives for refugees.

Wrapping up …

There has been relatively good progress on closing the vision and strategy gap, compared to the mainly humanitarian interventions at the beginning of the Syria crisis. In contrast, when looking at the humanitarian-development gap as a whole, the DEval-EBA study reveals that challenges in closing other sub-gaps remain. Moreover, with regard to the Syria crisis, there is no evidence on whether established linkages have generated positive effects for end-beneficiaries (i.e. Syrian refugees and vulnerable members of host communities). Thus, evaluations and/or impact assessments focused on outcomes are necessary. Also, such evaluative work should devote attention to political economy factors such as competition among departments and institutional path dependencies, which potentially hinder a more effective humanitarian-development linkage.

Alexander Kocks, Ruben Wedel and Hanne Roggemann are evaluators at the German Institute for Development Evaluation (DEval) in Bonn, Germany.

Helge Roxin is senior evaluator and team leader at DEval.

Contact: alexander.kocks@deval.org

Kocks et al. (2018), Building Bridges Between International Humanitarian and Development Responses to Forced Migration. A Review of Conceptual and Empirical Literature with a Case Study on the Response to the Syria Crisis, EBA Report 2018:02, Expert Group for Aid Studies, Sweden, and German Institute for Development Evaluation (DEval), Germany

This report can be downloaded free of charge at www.eba.se and www.deval.org

References

Hidalgo, S. et al. (2015). Independent Programme Evaluation (IPE) of UNHCR’s Response to the Refugee Influx in Lebanon and Jordan. Beyond Humanitarian Assistance? UNHCR and the Response to Syrian Refugees in Jordan and Lebanon, January 2013–April 2014. Transtec; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

OECD (2006). Whole of Government Approaches to Fragile States. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Darcy, J. (2016). Syria Coordinated Accountability and Lesson Learning (CALL). Evaluation Synthesis and Gap Analysis.

OCHA and REACH (2014). Informing Targeted Host Community Programming in Lebanon. Secondary Data Review. United Nations Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs; REACH.

Bouché, N. and Mohieddin, M. (2015). The Syrian Crisis. Tracking and Tackling Impacts on Sustainable Human Development in Neighboring Countries. Insights from Lebanon and Jordan.

Cullbertson, S. et al. (2015). Evaluation of Emergency Education Response for Syrian Refugee Children and Host Communities in Jordan. United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund.

Lee, B. and Pearce, E. (2017). Vulnerability- and Resilience-Based Approaches in Response to the Syrian Crisis: Implications for Women, Children and Youth with Disabilities. Women’s Refugee Commission.

Mowjee, T. et al. (2015). Coherence in Conflict: Bringing Humanitarian and Development Aid Streams Together. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, Danish International Development Assistance.

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment