Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Mechanisation – a catalyst for rural development in sub-Saharan Africa

Agriculture accounts for about 50 per cent of gross domestic product in Africa. The majority of the population – 80 per cent in fact – works in agriculture. Despite the sector’s significance, however, the level of public and private investment is insufficient to unlock its full potential. Strong population growth is putting tremendous additional pressure on the farming sector. Moreover, not only is the urban population growing apace (more people in Zambia now live in the cities than on the land) but the rural population is ageing: young people and the educated are migrating to the cities to seek new opportunities and to earn money. As the urban population grows, consumer spending habits also change. People’s appetite for protein in the form of meat and fish is soaring, particularly in many Lower Middle Income Countries (LMICs). Consequently the demand for agricultural commodities is also rising. Agricultural productivity in Africa is largely stagnating, and current supplies are unable to keep pace with the increasing demand. Higher prices could, however, act as an incentive for food producers to step up their output. These incentives would call for investment in infrastructure, education and service provision. Likewise, functioning institutions are indispensable if the rural population is to have access to natural resources (land, water), along with the capital they need to invest, and knowledge provided by agricultural advisory services. Further research into efficient cultivation methods, improved crop varieties and effective farm inputs is required, while more work is needed to improve the diffusion of promising technologies (including mechanisation options).

As a major agricultural production input and a catalyst for rural development, mechanisation endeavours to:

- increase the performance and efficiency of farming activities,

- create jobs (entrepreneurship) and sustainable rural livelihoods,

- promote agricultural development-led industrialisation and markets for rural economic growth,

- improve the quality of primary and processed goods,

- improve working conditions and raise living standards.

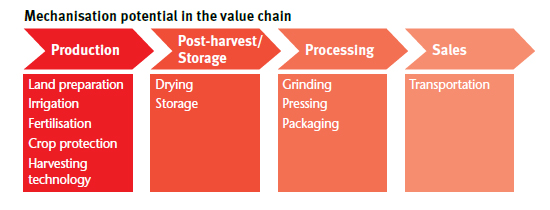

Mechanisation has a significant role to play at all levels along the entire value chain in terms of modernising and intensifying agriculture; it creates employment in rural areas – a core element of rural developement – and ultimately leads to food security

At production level, mechanisation is the key operational input for improving the productivity of both labour and land. Machinery efficiently prepares the land for planting without the physical workload, and at the same time ensures that production inputs are used effectively, so that the harvest is of good quality and quantity. Taking advantage of mechanisation at the growing, storage and processing stages also reduces post-harvest losses. A current GIZ study on post-harvest losses of potatoes in Kenya shows that 95 percent of potato damage and loss take place at production level and can be ascribed to inadequate harvesting technology and farmers’ lack of knowledge.

At post-harvest and storage level, a large proportion of production is lost as a result of improper handling and poor storage capacity. Good storage facilities in the form of silos and cooling systems help to reduce food losses and, by allowing farmers to sell their products later, help them fetch higher prices. Such facilities also play a crucial role in the context of food preservation and food security.

In the processing sector, the correct technology is a major factor of quality assurance, ensuring that the quality of the end products meets consumer demand at various different levels, and can thus be sold at a profit. In many cases, however, adequate machinery to process agricultural commodities – to grind the grain, press the oilseeds and produce starch from roots and tubers for instance – is simply not available.

Mechanisation and structural change

Mechanisation and structural change

There is no doubt that if mechanisation is to make a positive contribution to modernising and intensifying agriculture, then it must be introduced correctly. This means it must match local conditions, conserve natural resources and the environment, and increase production. Taking Germany as an example, today only 1.6 percent of the working population is employed in agriculture, forestry and fisheries, but one in nine jobs is associated with agri-business (upstream and downstream sectors). Over the last few decades, quality and processing of the food have improved dramatically. The huge rise in productivity is a result of labour-saving, highly efficient equipment and the mechanisation of agriculture.

The use of capital-intensive forms of production is thus considered the most important reason behind the fast-paced structural change in farming. To fund this equipment it was vital in Germany that cooperative associations and machinery rings were established. Machinery rings aimed at using the available machinery to capacity and developing additional sources of income have evolved in many regions. They have become a significant economic factor and have also created jobs in the service industry (maintenance and repairs, operation).

Worldwide trends clearly show that there are strong correlations between economic growth and mechanisation; countries which have experienced economic growth during the past 30 years and are tackling their hunger problem have also forged ahead with the mechanisation of agriculture. Countries where economic growth rates have been poor and poverty has remained high, however, have also lagged behind with agricultural mechanisation. If we take the number of agricultural machines in use as an indicator of the progress of mechanisation, then the following can be stated for the past 50 years:

Number of tractors in use (mil.)

| 1961 | 1970 | 2000 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 0,172 | 0,275 | 0,221 |

| Asia | 0,12 | 0,6 | 6 |

| The Near East | 0,126 | 0,26 | 1,7 |

| Latin America | 0,838 | 0,637 | 1,8 |

Compared with the other regions, Asia has seen the greatest rise in tractor numbers (including two-wheel tractors). Changing from the traditional labour-intensive production and post-harvest activities to labour-saving technologies was the continent’s answer to increasing workforce shortages, an ageing population and rising labour costs. This development shows the extent to which the region’s agriculture has been transformed during recent years. Investment in mechanisation has enabled farmers to intensify production, improve their quality of life and contribute to national and local prosperity. In countries such as India, China, Brazil and Turkey the rapid expansion in farm machinery demand has stimulated the growth of local machinery manufacture and given rise to an important sector of industry. These nations are now major producers of agricultural machinery. While South America and the Middle East have increased their use of farming machinery in recent years, in sub-Saharan Africa tractor numbers actually declined between 1970 and 2000. Even today historical patterns of subsistence farming prevail. The low levels of mechanisation and professionalisation of the sector are worrying. From the point of view of development policy, the solution clearly lies in formulating – and implementing – a national mechanisation strategy which is embedded in national agricultural policy. In the Philippines, for example, the Ministry of Agriculture pursues a mechanisation strategy which aims to increase the productivity and incomes of small farmers. Under this scheme, production machinery and post-harvest equipment are purchased from the National Rice Program budget and made available to qualified farmers’ groups, cooperatives and communities.

In many cases, however, mechanisation still fails due to a lack of funding opportunities. Individual farmers are not in a position to purchase the expensive machinery on their own. Moreover, in many African countries lack of access to land poses a huge problem, because this means that there is no chance of farmers obtaining credit. Frequently the available technology does not match local conditions and farmers’ requirements, and the farmers themselves are poorly organised. There is a great need for financial services to be made available to small farmers, and for cooperatives to be structured to make them an attractive option, thus allowing access to machinery. Training courses and organisational advice should also be made available to those wanting to upskill. The active participation of the private sector is further essential, for instance by providing after sales services (training, repairs, etc.). A lot can be learned from Asia’s experience in this respect.

Potato farming in Kenya

In Kenya the potato is an important staple crop which generates an income for more than 800,000 people. The market is growing rapidly as potatoes are becoming an affordable and thus sought-after source of food for the growing urban population. However, production is not able to keep pace with the increased demand. The majority of potatoes are currently produced by small-scale farmers on areas of land between one and five hectares. Most (80%) of the potatoes produced are still being sold through informal markets and consumed fresh.

Most farmers cultivate their land using traditional tools and production methods, which results in low yields (3-7 tons of potatoes per hectare), heavy losses and poor quality. The land is mostly tilled by hand with a hoe. This involves hard physical labour, and only the surface of the soil is tilled. Even where machinery is available, the farmers often do not know how to use it correctly. For example, tractors with disc ploughs are driven too fast over the ground, leaving it poorly prepared for sowing. Planting is also done by hand, which is a time-consuming and laborious task. The lack of storage facilities forces farmers to sell their products immediately after they have been harvested, which makes them unable to respond to market signals. To increase potato productivity and value, machinery should be utilised at the soil tillage and seedbed preparation stage. A tractor with planting machine can be used on small fields from about 0.2 hectares, but its use is only worthwhile if farmers’ organisational structures are in place. Crop protection measures should also be carried out using motorised sprayers or – on large fields – tractors. Additional irrigation systems extend the potato season. The use of such machines and creation of storage facilities (cooling systems) could stabilise the potato supply and achieve higher prices. For this purpose, it is essential that farmers organise themselves – in machinery rings/cooperatives or as contractors, for instance, so that they can share the investment costs – and that the mechanisation they opt for is compatible with local conditions and sites.

The Potato Initiative of the German Food Partnership

The Potato Initiative Africa (PIA) is a pilot project within the German Food Partnership (GFP), which was established in 2012 under the auspices of the German Federal Ministry for Economic cooperation and development (BMZ). Initially the PIA is focusing its efforts on modernising the potato sector in Kenya and Nigeria. Its aim is to develop an integrated concept promoting competitive value chains in the sector, which can then be extended to other regions, too.

To make full use of the countries’ potential and foster competitive value chains, new cultivation methods are being tested, opportunities to integrate small-scale farmers in local markets are being identified, and mechanisation options appropriate to local conditions are being introduced. Germany’s agricultural sector is involved in the initiative. Companies are making farming equipment and inputs such as seed potatoes, fertilisers, crop protection products and machinery available for testing on (small) farms to establish their potential to increase yields and incomes (see interview "Farmers have to get organised").

The table shows the machinery that was tried out during the current growing season. Its impact on yields and incomes is now being evaluated.

Machinery tried out in the Potato Initative Africa

| Step in production | Before | Now | Potential benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil preparation | Hoe | Rotary Hiller: For making the ridges |

|

| Soil preparation | Hoe | Bed Former: For making the ridges firm and solid |

|

| Planting | Hoe | Planter: For potato planting |

|

| Harvesting | Hoe | Harvester: For potato harvesting |

|

Thomas Breuer

Karina Brenneis

Dominik Fortenbacher

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH

Bonn, Germany

dominik.fortenbacher@giz.de

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment