Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Food system transformation needs private sector support

With the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), the world has laid out an ambitious plan to reduce poverty and enable people to live in dignity and security in a healthy environment. Joint efforts, including contributions from the private sector, are required to reach the estimated annual investments of 5,000 billion US dollars needed to meet the SDGs. Publicly available data reflects a huge investment shortfall to reach the annual goal; private sector contributions are currently in the range of one-digit shares, and only six per cent of official development assistance is targeted to leverage private investments. Today’s modest financial flows from private sector undertakings towards reaching the SDGs suggest a substantial growth potential of this form of collaboration in development cooperation for the good of people and environment. The Water Productivity project is an example where private sector companies engage financially in more sustainable agricultural value chains. They are the often “missing middle” in a food system ranging from producers to consumers. Below, we would like to share some insights gained from eight years of collaboration with private partners in the project, directly and in the frame of multi-stakeholder initiatives.

The Water Productivity Project

Aimed at enhancing water productivity in the cultivation of rice and cotton, two of the most water-consuming crops globally, the Water Productivity Project (WAPRO) consists of ten sub-projects active in six countries: India, Kyrgyzstan, Madagascar, Myanmar, Pakistan and Tajikistan. Mandated by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), Helvetas has coordinated project implementation through a “push-pull policy” approach. In its “push component”, which basically means the building of farmers’ capacities, it has worked with 80,000 farmers to help them adopt water-saving technologies. Through its “pull component”, which refers to the demand side of sustainably produced goods, global as well as smaller domestic companies are now sourcing rice and cotton more sustainably, encouraging supplying farmers by providing them with a market. The “policy component” addressed water stewardship at the field level, e.g. by supporting Water User Organisations and interventions towards a conducive policy framework in the regions and countries of intervention. To this end the project has contributed to shaping global production standards, influenced national and sub-national policies to allocate scarce irrigation water fairly, and empowered thousands of farmers to claim their right to access to irrigation water via local water stewardship actions.

Why cooperate with the private sector? Motivations …

Helvetas has around 40 ongoing projects covering agricultural value chains, private sector development and vocational skills development in which private sector partners engage. In the WAPRO project, the private sector companies contributed to the capacity building of producers and assured the demand for sustainably produced agricultural commodities. In terms of funding the initial investment of the donor, the SDC leveraged contributions from additional partners, including private ones, by a factor of more than three.

From the point of view of a development organisation such as Helvetas the motivation to enter such partnerships is the increased probability of a) reaching impact and scale, b) achieving sustainability of the results, c) finding innovative solutions, and d) leveraging public funding. From the perspective of participating enterprises, the following factors motivate them to engage: a) accessing new markets, b) complying with preferences of consumers and clients, c) meeting growing expectations from the public (reputation) and from the side of investors, d) establishing lasting relations to producers and collaborators, e) gaining improved access to thematic and technical competence, f) being involved in projects with high credibility and visibility, g) finding innovative solutions.

… and success factors

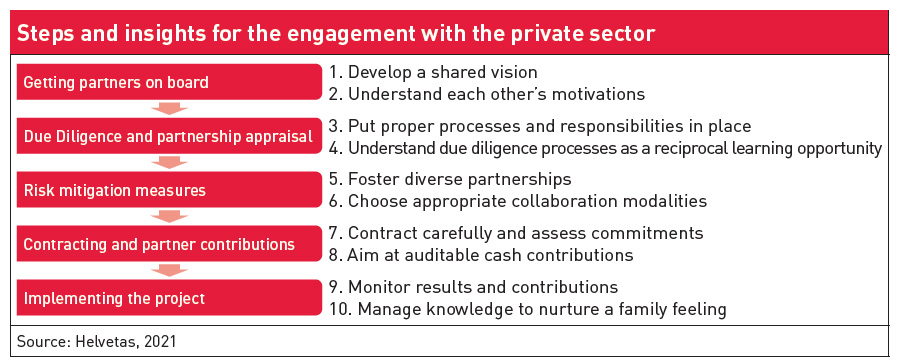

Practical experience yielded the following lessons for the success of collaborations between NGOs and the private sector (also see Figure):

There must be substantial overlap in the vision of each partner; divergences need to be known and declared. Ultimately, it is the shared vision among the power holders that really counts. Collaborators working in Corporate Responsibility Sections of private partners may be overruled by those who are responsible for economic transactions. Nor can NGO staff always succeed in getting their managers on board. It is just as important that overlaps exist in partner objectives, and that these are clearly defined in order to manage expectations and avoid disappointments, but also to build a relationship based on mutual understanding and trust.

Both sides want to know with whom they engage, and therefore conduct due diligence processes. As these processes take time, it is recommendable to establish standardised processes and conduct them early in the development of a partnership; furthermore, mitigation measures for identified risks (e.g. disregard of human rights, inefficient/fraudulent use of public funds, reputation risks due to sustainability challenges) and a reporting mechanism should be put in place. Perceiving due diligence processes as a reciprocal learning opportunity may nurture mutual understanding and lead to less resistance to them on both sides.

To work with more than one private sector partner in each project is enriching and prevents project success from being associated with only one private partner. Equally, private partners may prefer not to put all their eggs into one basket. Measures such as starting small, avoiding the flow of funds between either party in case of looming reputational risks and defining red lines which, when crossed, result in collaboration being terminated, may help to contain risk.

When it comes to contracts between private sector partners and traditional development actors, different cultures may clash. Partners should be prepared to conduct intense negotiations involving legal counsel. If premium prices (e.g. for organic or Fair Trade products) are intended to count as private partner contributions, this needs to be expressly stated. Contractually fixed volumes of traded goods (e.g. tons of an agricultural good procured) should serve as targets rather than contractually binding terms, as the private partner will only buy what the market demands. In partnerships with large companies, a contribution in cash (not only in kind) should form part of the deal. The contribution must be verifiable through the company’s audit report. If there is a flow of money to the private sector partner, there must be a verifiable public benefit.

Content and frequency of monitoring and reporting needs to be contractually agreed. This also applies to agreed financial contributions. In the case of public or philanthropic funding flows to private partners, it is important to agree on milestone payments against well-defined achievements. One of the distinct advantages for private partners entering development-oriented collaboration is the opportunity to learn from other companies and sectors. Therefore, the management and exchange of insights deserve particular attention. International NGOs and multi-stakeholder platforms are well positioned to facilitate such processes.

The strengths of multi-stakeholder initiatives

One of the fundamental hypotheses at the start of the WAPRO project was that its ambitious goals regarding outreach and impact would only be achieved through collaboration involving multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs). MSIs bring together different stakeholders to deal with topics of mutual concern or interest. To foster the shared concern, they often develop a standard, support its application by the stakeholders involved and arrange for verification of compliance.

The three MSIs that engaged in the WAPRO project (see Box) unite businesses, civil society organisations and government representatives on a global level under the shared objective of making the world a more sustainable and fairer place. The Better Cotton Initiative (BCI) and the Sustainable Rice Platform (SRP) are organised along globally relevant commodity value chains, while the Alliance for Water Stewardship addresses core concerns for the joint interests of the involved parties, namely water stewardship. The MSIs foster interaction and learning guided by a transparent governance system. All three of them develop standards of their own which they hold the rights to. Their application by value chain actors combined with an independent mechanism for verification of compliance aims at a more sustainable use of resources to the ultimate benefit of producers, consumers and the planet.

WAPRO and its partners

The SDC-Helvetas WAPRO project collaborates with international private sector partners such as Mars and Coop, numerous local private and civil society partners as well as the following multi-stakeholder initiatives:

The Alliance for Water Stewardship – a global membership collaboration comprising businesses, NGOs and the public sector. Its members contribute to the sustainability of local water resources through the adoption and promotion of a universal framework for the sustainable use and management of water – the International Water Stewardship Standard, or AWS Standard – which drives, recognises and rewards good water stewardship performance.

The Better Cotton Initiative – the world’s leading sustainability initiative for cotton. Founded in 2005, its mission is to help cotton communities survive and thrive, while protecting and restoring the environment. Better Cotton partners include farmers, ginners, spinners, suppliers, manufacturers, brand owners, retailers, civil society organisations, donors and governments, adding up to more than 2,300 members to the Better Cotton network. They buy into Better Cotton’s approach of training farming communities to produce cotton in ways improving things for everyone and everything connected with this staple fibre.

The Sustainable Rice Platform – established in 2011. Together with its over 100 institutional members from public and private sector stakeholders, research, financial institutions and NGOs, the Platform aims to transform the global rice sector by improving smallholder livelihoods, reducing the social, environmental and climate footprint of rice production and offering the global rice market an assured supply of sustainably produced rice to meet the growing global demand for this staple food.

Cooperating with the three MSIs rests on the following assumptions. On the “push” side, the introduction of and compliance with the MSI’s standards provides guidance for the producers. Moreover, the interaction with manifold partners in the frame of the MSI helps to reach scale. And the MSI fosters the expected compliance with the standards, thereby contributing to the sustainability of the interventions. On the “pull” side, the MSIs are seen as the vehicle to assure a growing market for more sustainably produced goods, beyond the lifespan of a development project. The exchange with other members of the MSIs allows for crowding in of new partners. As regards “policy” influence, the MSIs are seen to potentially serve as a platform to raise awareness among government representatives of policy gaps that prevent the efficient use of water. SDC, as a donor, and Helvetas, as an implementing international NGO, recognise engagement with MSIs as an opportunity to influence global standards.

One crucial benefit of MSIs from a development perspective is the assurance of sustainability in the long term. Even though a development project may have ended, the value chain partners continue to follow the standard, thereby ensuring sustainable production. In return, by joining WAPRO, the three MSIs saw an opportunity to increase the application of their standards, to further develop their standards based on field-level experience especially among smallholders in the Global South and to shape strategies of participating members, including donors and NGOs.

… and challenges of MSIs

A reflection among Helvetas and the MSIs involved in WAPRO identified four main challenges for successful sustainable multi-stakeholder partnerships:

Representation of producers. Assuring a true and meaningful participation of primary stakeholders (the producers of agricultural commodities) in decision-making processes of MSIs and avoiding power asymmetries remains a challenge despite all goodwill and efforts. The MSIs partnering in the frame of WAPRO address this issue through reserved seats in their governing bodies respectively through the expectation that NGOs such as Helvetas defend the interests of the primary stakeholders. In addition, the periodic review of the standards is organised in such a manner that primary stakeholders can express their point of view.

Stringency versus scale. The standards of the MSIs have different ambitions regarding stringency. As a promoter of organic agriculture, Helvetas experienced this situation itself, which triggered internal discussions. The commodity standards BCI and SRP are committed to sustainable production but do not promote pure organic production methods. Ultimately, it is the market, respectively the consumers, who define which standard is reaching scale. The WAPRO project provides evidence that among participating farmers a gradual shift from softer towards more stringent ecological production practices happens, if supported with knowledge exchange and learning within and across MSIs. This was, for example, the case in the WAPRO sub-project in Pakistan, where farmers adopted biological pest control measures.

Reputational risk of being associated with dishonest MSI members. Even with the best standard and assurance system, an MSI may be abused as a fig-leaf to hide violations. Beyond well-functioning compliance and governance processes, dealing with this uncomfortable situation requires clearly communicating what an MSI stands for and ensuring the continuous improvement of the system in response to what has been learnt in the field and from exchange with others. To this end, the WAPRO sub-projects – and of course others – served as testing ground for the two commodity standards for rice and cotton.

Assured compliance in times of rapid growth. To assure compliance in times of rapid growth is a challenge to any standard. The answer to this challenge lies in the periodic revision of the standards and collaboration with specialised organisations to monitor compliance. To this end, WAPRO, for example, served as a vehicle to integrate the aspect of water stewardship into the Better Cotton standard.

Summing up

The participating organisations experienced the collaboration with and among three MSIs in the frame of WAPRO as being beneficial for all involved. The initial hypothesis that MSIs can serve as a vehicle to reach scale held true. Over 80,000 rice and cotton farmers in six countries are now applying more water-efficient irrigation techniques and have thereby increased their incomes. By bringing together producers and buyers the commodity-based MSIs Better Cotton (BC) and Sustainable Rice Platform (SRP) play an important role in ensuring markets for participating farmers. In the case of SRP – whose assurance scheme was launched only in 2020 – there is still considerable scope for market growth and upscaling. It is for example only a recent achievement that SRP-labelled rice can be bought in European supermarkets such as Germany’s Lidl and that the leading Italian grain brand, Riso Gallo, is SRP-labelled. Both MSIs offer solutions for the marketing of smaller quantities, too, which results in a market-levelling effect to the benefit of smaller producers. For example, the SRP member “Rice Exchange” has developed a digital blockchain-enabled rice trading platform that also allows matchmaking between smaller SRP-compliant producers with global customers.

The project organised periodic implementers and partner meetings, thus serving as a forum for cross-fertilisation among the MSIs, which helped to improve standards but also provided insights into the strategic thinking of Helvetas, particularly with regard to its engagement with private sector partners. The main insight stemming from the discussion of the four challenges faced is that multi-stakeholder initiatives and their standards are, and have to be, learning organisations that improve their governance and tools based on the feedback from their stakeholders, including the primary producers.

An engagement of private partners is essential for reaching the SDGs in general and for contributing to the financing of food systems in particular. Therefore, Helvetas seeks collaboration with private partners based on its long experience and proven skills, while respecting due diligence requirements. The example of the WAPRO project has confirmed that a carefully managed collaboration between private sector companies and development organisations leads to impact at scale, sustainability of the results and innovation.

Peter Schmidt is Senior Advisor Agriculture and Food at Helvetas, which is based in Berne, Switzerland.

Contact: peter.schmidt(at)helvetas.org

Jens Soth is Senior Advisor Value Chains/ Sustainable Commodities at Helvetas.

Contact: jens.soth(at)helvetas.org