Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Towards inclusive and sustainable contract farming

Vietnam is known as a global supplier of low and medium-quality rice. The low-quality rice provides an affordable staple to countries that need to prioritise food security. On the other hand, Vietnam also exports quality rice to more demanding consumer segments in Europe and the USA. Rice consumers pay attention to quality, brand, reputation and product traceability; for example, urban consumers in Vietnam exhibit preferences for rice which is produced using sustainable methods (also see Rural 21, no. 4/18, p. 37–39). With this, Vietnam became supportive of producing higher quality and sustainable rice. Entry points in producing sustainable rice are now being streamlined through national programmes encouraging the production of high-quality rice complying with sustainable production standards such as “One must do, five reductions” (also see Rural 21, no. 3/21, p. 40–41) and scaled through horizontal coordination mechanisms such as the “small farmer, large field” programme. These will be used for crafting global standards on environmentally sustainable rice production such as the one promoted by the Sustainable Rice Platform (SRP; see www.sustainablerice.org), a global multi-stakeholder alliance. This effort presents an opportunity to Vietnam given the rising demand for sustainably-produced products in local and global markets.

Contract farming as an entry point towards sustainable rice production

Implementing a national programme on sustainable rice production in Vietnam aimed to motivate farmers to reduce chemical use. This was complemented by enhancing research on sustainable practices and standards and launching training programmes to improve the skillset of extension workers and farmer groups to comply with sustainability standards. In the context of the programme, discussion platforms were set up for farmers and other sectors to elicit issues and determine opportunities for strengthening linkages among rice value chain actors.

Contract farming is gradually being adopted by rice export companies. It is is one mechanism for promoting sustainable rice production in Vietnam via farmers’ participation through strong linkages and coordination among farmers as suppliers and food companies as buyers of sustainably-produced rice. The contract enables food companies to govern rice quality and tailor it to their customers’ needs. Such a mechanism can encourage the companies to provide production support to farmer groups and improve their access to better quality agricultural inputs, technical support, storage facilities, and secured output markets. Through support of this kind, companies such as the Loc Troi group have been able to successfully encourage farmer groups to adopt sustainable rice quality standards.

Ideally, farmers should be able to negotiate mutually beneficial contractual arrangements. Trust among farmer groups and food companies is essential to ensure adherence to contract terms and certification schemes, resulting in the production of environmentally sustainable and premium quality rice. The arrangement becomes inclusive if the active players can effectively influence contract terms.

Fostering inclusiveness of contract farming

Creating a safe, transparent and enabling environment for negotiation can help craft an ideal contract between farmers and food companies that is inclusive and promotes sustainable production standards. This can help support both parties in negotiating the details of the contract, and discuss the regulations, policies, and institutions that need to be introduced or modified. For this purpose, the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) organised a multi-stakeholder participatory workshop in October 2018 during which it set up a negotiating platform among 73 participants which included farmer groups, the Provincial Project Management Unit (PPMU) and food companies in the Mekong Delta.

The negotiation process revolved around eight contract attributes:

- Price premium: the price incentive that the two parties will agree on, conditional to farmers complying with the terms and standards stipulated in the contract.

- Pre-financing mechanisms: the extent to which food companies pre-finance inputs such as seed, fertilisers, pesticides or credit.

- Flexibility: the degree to which contract terms can be modified to farmers’ preferences (e.g. flexibility in choice of chemicals).

- Quality of rice: the quality class both parties agree on (e.g. low-medium, high-quality or premium rice).

- Production standards: sustainable production standards, free of pesticide residue, etc.

- Private extension: food companies hire their own extension workers who provide technical assistance to farmers in order to ensure that farmers adhere to the production standards.

- Paddy storage facility: food companies provide a storage facility where farmers can store the products interest-free while waiting for better market prices.

- Production season: the rice production season to which the contract applies (e.g. winter-spring or summer-autumn season).

The workshop participants were also encouraged to add their own preferred attributes in their ideal contract and identify changes needed in the enabling environment (e.g., regulations, policies, etc.).

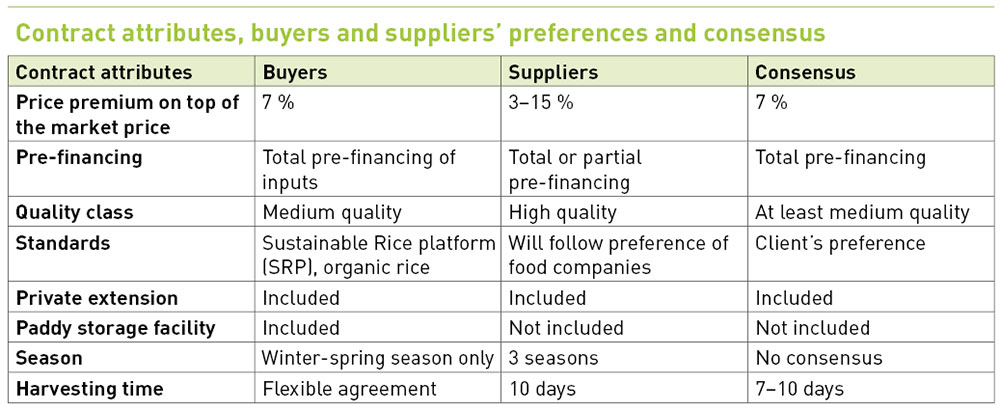

Negotiations during the workshop took place in the form of moderated plenary discussions between spokespersons of farmer groups (suppliers) and food companies (buyers) in order to achieve consensus on the agreed contract terms (also see Table below). There were several points of contention, among them the price premium that would incentivise farmer groups to comply with sustainable production standards. The optimal level of pre-financing was also heavily debated among suppliers, who had diverging preferences.

Some farmer groups favoured total pre-financing (of seed, fertilisers, and pesticides) from the food companies, while others opted for partial pre-financing to maintain some flexibility in the choice and cost of inputs (brand, dose, etc.). The season was also a point of contention; while farmers preferred to receive a contract for all three production seasons, food companies were only interested in the winter-spring season, as this season features the lowest production risk. Remarkably, there was little discussion on compliance with sustainable production standards; farmers claimed to be happy to follow the preference of food companies, as long as they are incentivised.

After negotiation, representatives of farmers and food companies achieved consensus on several attributes of a sustainable contract. Both parties accepted a seven per cent price premium and total pre-financing of a fixed package of seeds, fertilisers and pesticides without flexibility in the choice of the brand or dose of chemicals. Food companies will also provide credit, but it will be under control of the farmers’ organisation. It was also agreed to produce medium-quality rice following the rice production standards set by the client and harvest time to be announced seven to ten days before harvesting to provide ample time for the food companies to secure the necessary arrangements.

Changes in the enabling environment that were recommended included creating mechanisms to foster better understanding of policies, enhancing participation by farmers and improving capacity building skills of cooperatives.

Lessons learnt

To support positioning Vietnam as an exporter of sustainably-produced rice, farmers need to be provided with the right incentives to comply with sustainable production standards. Creating an inclusive contract requires a safe space for rice stakeholders to negotiate contract terms that are mutually beneficial for buyers and suppliers. Pre-financing enables exporters to govern agricultural input use, product quality and production standards. This can decrease the use of harmful chemicals and reduce environmental footprints. The negotiated “ideal” contract is already being adopted by certain food companies, such as shown above with the Loc Troi group, and can serve as a champion or blueprint for future negotiations between food companies and farmer organisations. It will help enhance the goals of inclusive contract farming and generate optimal gains not only for both suppliers and buyers, but also for the environment. It should be taken with a caveat, however, that farmers may lose some autonomy in the process as governance of production (and production risk) is gradually shifted towards food companies.

In the long term, the promotion of sustainable practices in rice production and the growing consumer preferences for sustainably-produced rice can serve as opportunities for farmers to build brands of their own through certified sustainable production labels. Encouraging farmers to create their own brand will enhance their competitiveness, but requires increasing farmers’ organisations’ capacity in branding, management, and trading. This includes adopting quality standards complemented by establishing protocols, and allocating adequate resources and facilities that will improve the groups’ rice processing facilities and food processing. A continuous chain of capacity building can be developed and scaled out to other farmer organisations in the Mekong Delta who are keen to develop their own rice brand satisfying sustainable rice production standards. Lastly, developing prototype brands and testing them in urban markets to elicit consumer response could help in identifying the right move to link the products to the markets.

Reianne Quilloy is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Science Communication/ College of Development Communication, University of the Philippines, Los Baños.

Matty Demont is the Research Leader on Markets, Consumers, and Nutrition at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI).

Phoebe Ricarte is an Assistant Scientist on Market and Food Systems Research at the IRRI.

Contact: rmquilloy@up.edu.ph