What works in rural (youth) employment?

The population in Africa will double by 2050, the average sub-Saharan African is about 18 years old. Every year, 25 million new jobs need to be created for young people entering the labour market in Africa. A large proportion of them live in rural areas. With both a fast-growing demand for food and under-utilised resources, the agri-food sector has by far the largest potential to create additional employment opportunities, as shown in recent studies, e.g. by OECD-SWAC on “Agriculture, Food and Jobs in West Africa”. However, major challenges need to be addressed. Rural youth often see (traditional) agriculture as a less attractive, low-opportunity occupation with high risks and drudgery owing to outdated working practices. They tend to be biased towards white-collar jobs in urban areas. Additionally, access to education and training, advice and services (especially financial services), land, markets and networks, physical and digital infrastructure and technologies is comparatively weaker than for more experienced adults and their urban peers. Young rural women are affected disproportionally with a “triple burden” as framed in IFAD’s 2019 Rural Development Report.

In order to better understand what works in rural youth employment promotion, eleven programmes being implemented by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) in Africa have been analysed in the context of a stocktaking study. The programmes cover a wide range of global, continental, regional and bilateral projects against the background of different development approaches e.g. rural and value chain development, vocational training and private sector cooperation as well as national employment policies. Based on eleven case studies focused on the African continent, the study presents systematic insights on how projects address the issue and what can be learned from that for future strategy and portfolio development.

Adapting the integrated approach to the context of rural areas

In German development cooperation, an integrated approach has proven to be useful in employment promotion. In a nutshell, it connects the main elements of labour demand and labour supply with matching services and an enabling environment. Nonetheless, given the distinct characteristics within the agri-food sector, the approach needs to be adapted regarding a number of key aspects related to the specific features of rural economies.

First, in rural settings, informal and entrepreneurial training approaches take a higher priority on the supply side of the labour market than formal vocational education and training. Secondly, small and micro-enterprises and smallholder farmers with a high share of self-employment and family labour play an important role on the demand side of the labour market. Thirdly, due to limited institutional capacities and public services in rural areas, matching services are much more challenging and should include the matching of labour (e.g. access to freelance work, job placement, internships) as well as products and services (e.g. farmers' access to markets for their products). And finally, the addition of “labour market foundations” addressing the inclusion of young rural women, changing the perception of agriculture as well as building the right meso-level support structures (including e.g. strong youth networks, training and incubation centres, etc.) is important in complementing the key interventions in promoting skills development and business opportunities.

Key success factors

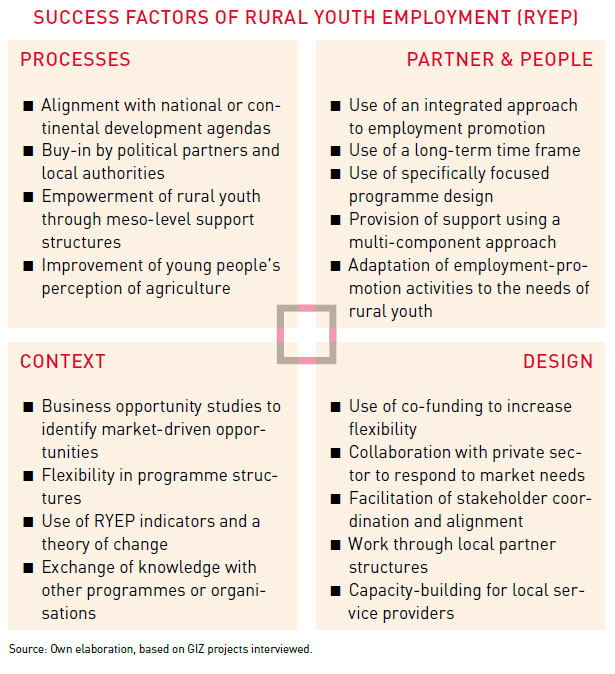

Derived from the detailed analysis of good practices and lessons learnt from each case study, 18 success factors have been mapped and clustered along four project dimensions (see Figure). While several of the success factors are specific to rural youth employment, others are relevant in the broader context of rural development or employment promotion programmes or even development projects in general. By further generalising these success factors, four main aspects are of particular importance as they played a crucial role in nearly all the programmes and represent, as it were, core standards that every project on rural youth employment should consider:

Leverage local partner structures to strengthen youth as key actors for development. To be successful in a complex topic like rural youth employment promotion, programmes should pay attention to relevant context factors. This can be achieved, e.g. by close alignment with national or continental development agendas. Fostering buy-in and ownership of (political) partners and promoting activities that cultivate trust between rural youth and political decision-makers can be of additional value. Projects must promote a sense of shared stakeholder ownership and collaboration in local ecosystems and multi-stakeholder platforms. Embedding programmes in national policy frameworks, e.g. the integration of agricultural curricula into national education frameworks, may add to their complexity, but it usually pays off by contributing to efficacy, sustainability and the potential for upscaling.

Acknowledge the employment realities and needs of rural youth and work with multi-component approaches. Since youth in rural contexts usually face a wide range of specific and interrelated challenges, programme strategies and design factors should include a multi-component or “integrated” approach, addressing key factors of skills development, enterprise development and matchmaking services. Thus, it is paramount to adapt and tailor formats and delivery modes to local conditions and employment needs, especially as the rural youth are no homogenous group. Youth organisations and networks play an essential role in involving young people in decision-making processes. They should, therefore, be an integral part of the stakeholder landscape.

Transform the image of agriculture – from subsistence agriculture to profitable business models. Offering youth a broader view of the agri-food sector, especially on attractive on- and off-farm job opportunities along value chains, can help to spark their interest. Drafting specific business-opportunity studies and setting up flexible implementation structures allow projects to identify and build service offers around context-specific business models. Programmes can promote the development of modern and innovative agri-food networks, including parties who grow, harvest, process, package, transport, and market agricultural products, consumers, restaurants and waste disposal, too. Supporting awareness campaigns and successful “agripreneurs” as role models and mentors will help in transforming the perception of the sector and developing productive employment opportunities.

Strengthen multi-stakeholder coordination and cooperation with the private sector. Programme activities should be well-coordinated and agreed with the diverse range of relevant public and private stakeholders to capitalise on existing resources. In this way, they can break up so-called silo thinking and facilitate the creation of coherent support services. Private sector perspectives are particularly relevant for the selection and development of employment-intensive value chains as well as for needs-oriented curricula and qualification offers. Market-driven approaches help to identify robust business models with relatively low risks and investment costs that are suitable for young entrepreneurs. The private sector is also crucial to harnessing the expertise and, finally, to mobilising resources for investments in job creation and income generation.

Further recommendations and key takeaways

Building on the results outlined above, there are two main recommendations for shaping youth-specific interventions as well as the overall portfolio for rural youth employment promotion. First, it is important to address employment promotion more holistically, combining activities on the supply side and demand side of the labour market. For successful employment creation, all elements of the integrated approach should be comprehensively analysed and addressed if necessary. However, this does not mean that everything needs to be realised within one project or institution alone. It is crucial to take the distinct characteristics of employment in rural areas into account and shape approaches accordingly. Secondly, depending on specific contexts and target group demands, policies and programmes need the right balance between mainstreaming youth aspects in broader economic development promotion and developing youth-specific solutions to address challenges such as access to information, land, capital and markets. Both are necessary to capitalise on the manifold opportunities that the agri-food sector offers to contribute to a true "youth dividend”.

To really answer the question “what works in employment creation”, further research and more systematic knowledge management will be necessary. Only comprehensive programme evaluations will allow for a deeper understanding of the most effective approaches to create broad-based employment opportunities and to achieve scalable impacts. However, it is interesting to already see the different types and scales of results, outreach, and impacts on rural youth employment and beyond, that the projects achieve in their specific contexts. The study also outlines a couple of additional open questions for further research, e.g. on the impacts on land rights, the prevention of a brain drain, effects of mechanisation and digitalisation, or the quality (and future) of work. In this sense, the results of the study represent an important, albeit only initial step for future strategy development and project design, helping to shape development programmes and investments in the field of rural youth employment promotion. Besides the suggested research, it would also be of interest to broaden the regional and institutional scope of the analysis by including experiences of other institutions who are likely looking for similar answers.

Julia Müller is a Junior Advisor at the Global Project Rural Youth Employment of Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH and is based in Bonn, Germany.

Contact: julia.mueller@giz.de

Frank Bertelmann is Head of Programme of the GIZ Global Project Rural Youth Employment.

Contact: frank.bertelmann@giz.de

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment