Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Trade and development – growing closer for sustainable rural transformation

Trade and inclusive agri-business for job creation and sustainable economic growth have a new impetus in the context of rural poverty, high rural unemployment in developing countries and growing concerns about economic migration. Value-chain development and value addition of agricultural produce are of increasing importance in meeting the rapidly growing demand of the urban population. Africa is focusing on a return to self-sufficiency in food supply which the continent lost in 2000 due to decreasing food prices in the nineties and failing investments into agricultural transformation by the farming community, international finance institutions and governments. Along with Africa, Asia and Latin America find greater opportunities in supplying local, national and regional markets with all products along the value chain than in investing more heavily into export or cash crops like coffee or soy beans. But do international consensus and trade agreements support local and national trade agendas?

Many Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and their targets and indicators call for an end of trade restrictions and distortions, agree on special and differential treatment of the trade regime for developing and least-developed countries and advocate poverty reduction through inclusive value chains and trade. However, the World Trade Organization (WTO) Doha round and numerous current free-trade agreements such as the mega-regional European Partnership Agreements (EPA) between European Union and ACP countries find profound difficulties in agreeing on terms of trade in agricultural produce like phyto-sanitary standards as well as protective measures to overcome the lack of competitiveness in agricultural production in developing countries.

The “Nairobi Package” on agriculture at the WTO’s 10th Ministerial Conference in December 2015 ultimately included a special safeguard mechanism on export subsidies and other export competition elements (particularly in cotton trade) for developing countries to become more competitive – the most significant outcome on agriculture for 20 years, many negotiators found. Progress in making international agreements beneficial to rural communities is slow.

What role does trade play in poverty reduction?

The logic of applying a markets and trade paradigm to agriculture is hard to fault. Ultimately, the livelihoods of three or four billion people at the bottom of the economic pyramid depend on the farming business. Agriculture is largely a private sector activity (even poor small-scale farming can be a business beyond subsistence), and the growth in demand for food in urban centres is creating substantial new market opportunities. While there is a clear rationale for mobilising trade, private sector investments and innovative financing for economic growth, the development objective of tackling poverty remains fully valid for the international community. However, it is yet to be shown how effective the trade-based approach is in providing benefits for vulnerable groups like subsistence farmers at the bottom of the economic pyramid or for redressing growing inequality of the rural-urban divide.

The critics, of whom there are plenty, argue that such approaches bear a high risk of exacerbating rather than overcoming exploitation of the poor. This behoves those advocating for a new development paradigm based on markets, trade and the private sector to be rigorously explicit about their “theories of change”or development cooperation strategies, formally based strongly on poverty reduction. An interesting policy analysis by the World Bank and the WTO suggests in The role of trade in ending poverty that careful crafting of balanced policies will bring the inclusive benefit sharing of trade and value-chain development closer to the bottom of the economic pyramid. But the devil is in the detail. What does “inclusive” really mean for the agriculture sector? And what is the long-term vision for a sustainable food system and the economic transformation of small-scale agriculture? These are not simply technical questions, they are deeply political and are often approached with strong ideological positions that have significant implications for national, regional and global trade policy.

What changes are already on the way?

Official development assistance (ODA) or development financing is increasingly small compared to other financial flows like foreign direct investments, domestic investments, remittances, etc. This has led many donors to focus more on how they can partner with international trade institutions under the “Aid for Trade” initiative and catalyse private sector investment and consequently increase ODA impact on economic growth. They want to articulate more openly that ODA can – inter alia – bring mutual benefit through improved trading relations between developing countries as well as between donor and developing countries.

While the International Trade Center (ITC) provides Market Analysis Services with a wide range of data, WTO offers its mandated support services and hosts a number of instruments like the WTO “Bali Package” on trade facilitation of border controls and customs services, the phyto-sanitary stand-ard setting/application for improved value-chain development through the Standards and Trade Development Facility (STDF) as well as trade co-ordination of all relevant sectors and their productions by the Enhanced Integrated Framework (EIF). Many more support mechanisms, programmes and initiatives of bilateral donors and international finance institutions (IFI) exist, but regional economic communities (REC) with a trade mandate are also improving their services significantly in order to link agricultural production more effectively to markets.

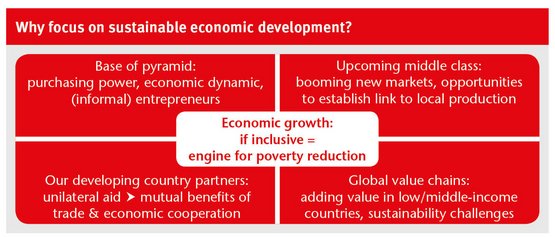

The governments of Australia, the Netherlands and Canada were the first to “amalgamate” foreign affairs, trade and development. Australia has a Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade that includes the development co-operation portfolio, Canada has created a Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development, and the Netherlands has established a ministerial office on trade and development in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. These are clear institutional signs of a profound change in policies of development co-operation. The Graph below gives four reasons to focus development co-operation and ODA on economic development. It neatly summarises the paradigm shift among some donor agencies, with an increasing number of donors following suit.

Inclusive agri-business – translating trade into benefits for rural communities?

Based on the new focus on trade and markets of the international development community, the concept of inclusive business in general has gained much traction for sustainable development – the promise of a win-win situation through profitable business activities that also meets the needs of the poor and helps to lift them out of poverty. In order to frame the term, an inclusive (agri-) business benefits poor producers and consumers by providing access to markets, services and products in ways that improve their livelihoods, while at the same time being a profitable commercial venture. Inclusive agribusiness offers a perspective that can contribute to a deeper understanding of how to align public and private interests and investments in pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The inclusive agri-business concept is highly relevant to the agricultural sector because of the vast number of small-scale producers and micro-enterprises and the potential for off-farm rural employment in value adding and upstream agri-food enterprises. Finding ways to ensure that agri-businesses help create fair economic opportunities for those lower down the economic pyramid is a key to ensuring trade impacts on poverty and inequality. Inclusive agribusiness is not just about the big end of town and global markets – it involves the interactions of micro, small, medium and large-scale business operating across domestic, regional and global markets, which from a trade perspective is critical to realise.

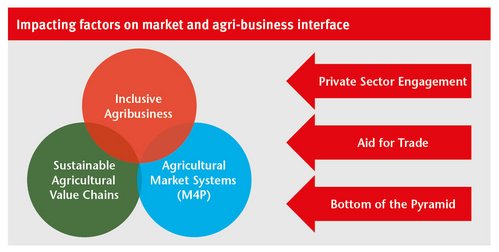

There are thousands of value-chain and market development projects that have inclusive elements. Many agri-business firms have initiated inclusive practices. There are active business platforms, such as the World Economic Forum with its Grow Africa and Grow Asia initiatives, the Sustainable Agriculture Initiative (SAI) Platform or the various commodity round tables (palm oil, soy, sugar, cotton, fisheries, etc.). National political leaders are taking up the importance of agriculture for inclusive growth and the need for new forms of partnership with business. Behind all this is much support of bilateral donors, multi-lateral agencies, development banks and philanthropic contributions with a very diverse range of multi-donor financing mechanisms and strategies such as the Global Agriculture and Food Security Program (GAFSP) and the African Enterprise Challenge Fund. The Graph below presents the impacting factors like private sector engagement of any scale, ODA interventions like Aid for Trade and the poverty dimension on the market and agri-business interface.

In the development sector, there has often been much attention in the past for social and environmental concern and related farming systems and only more recently for value-chain development within the broader trade agenda for economic growth. Inclusive agri-business strategies and policies offer ample opportunities for the donor community and IFIs to engage with small and medium-sized enterprises as well as multi-national companies in an operational way without losing sight of a sustainable rural transformation agenda with its social and environmental safeguards.

Paradigm shift or just changing policy priorities in development?

It is argued that the new development focus on trade and value-chain development as a primary means for economic development stands for a general shift in development paradigm with new roles of business, governments and the international community. This is in part a reaction of the international community to development trends in partner countries. Almost 30 per cent of ODA is currently spent on operations under “Aid for Trade”. However, to date, the potential for economic growth through agriculture is not sufficiently explored and used in developing countries despite cash crop exports like palm oil, coffee and tea or an increasing urban demand for food. Agriculture and rural development has not yet become a permanent top priority in development co-operation and national development programming.

The nexus of rural development and trade is therefore undernourished despite all the opportunities – much co-operation and mutually supportive policy work is still ahead for all actors to make full use of the trade potential for sustainable rural livelihoods. Trade in agricultural produce is a very complicated domain, and the rural development community needs to make careful and good use of the trade-related instruments, programmes and strategies to enhance inclusive rural transformation.

Policy coherence – bringing the communities together

In order to address the new focus of development co-operation on economic growth, attention should be concentrated on balancing economic development and social and environmental sustainability. The concept of policy coherence has been debated broadly to address the emerging rural development-trade interface. To fill such a concept with operational life, partner countries and donor agencies have to compare notes on enabling farmers and rural entrepreneurs to enter competitive markets and on the other hand focus on poverty reduction and local development priorities. Beyond the policy debate, institutional arrangements like inter-ministerial dialogues etc. need to be put in place for joint strategies and programmes of the trade and agriculture & rural development (ARD) community. The Global Donor Platform for Rural Development (GDPRD) was asking “Agricultural trade and rural development: Duet of Solo playing?” at its Annual General Assembly 2016 and is continuing the discussion on aligning ARD and trade policies. The Platform’s objective is to determine future donor programmes as well as multi-sectoral co-ordination within the respective donor agencies themselves in order to increase the development impact through new forms of ODA programming. Not only does this mean profound changes in co-operation and co-ordination in developing countries, but it also calls on donor agencies and IFIs to improve their own in-house co-ordination and inter-sectoral policy coherence. All development partners still have quite a long way to go to effectively support inclusive and sustainable rural transformation.

Christian Mersmann

Policy advisor

Global Donor Platform for Rural Development

Bonn, Germany

christian.mersmann@donorplatform.org

Jim Woodhill

Independent consultant

Inclusive agribusiness and rural development

Oxford, Great Britain

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment