Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Tackling food losses: New approaches needed

Food shortages, food price rises and the impacts of climate change on agricultural production are once again topical issues. In consequence, policy-makers, researchers and the private sector are turning their attention to the promotion of agriculture in developing countries. In 2009 the G8 countries launched the L’Aquila Food Security Initiative (AFSI), under which they pledged to provide 22 billion US dollars between 2010 and 2012 for measures that would help to permanently resolve the food crisis. The German chancellor, Angela Merkel, promised that during this period Germany would contribute three billion dollars for rural development and food security. The German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) has set out its targets for the promotion of rural development and food security in a ten-point programme. Among other issues, the programme explicitly refers to “improving post-harvest protection”.

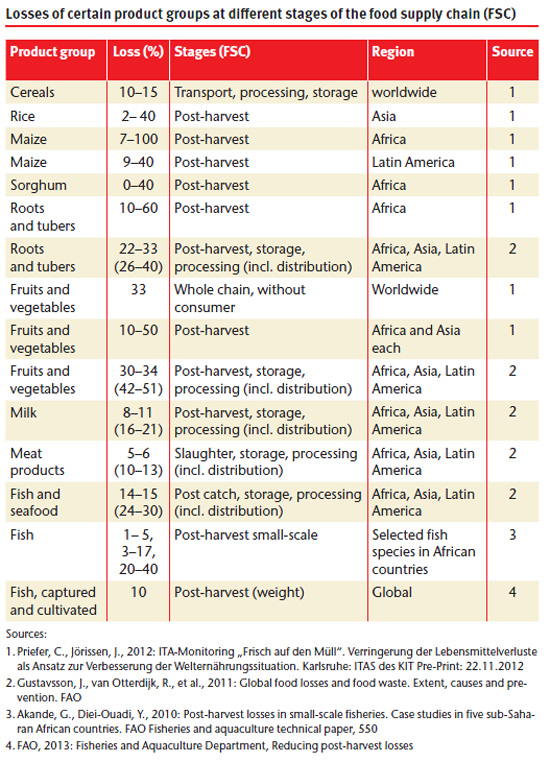

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that around 30 per cent of the food harvested worldwide is lost or wasted. This is equivalent to a staggering 1.3 billion tons (FAO, 2012). Similar figures were being quoted two decades ago and the present data basis is week. What is clear, however, is that food losses are making a significant contribution to the global food crisis.

Food losses occur along the entire food supply chain (FSC), including production, storage, processing and distribution, from the field to the plate. They are unacceptable from both economic and environmental points of view since they vitiate investment that has already been made in agricultural inputs, labour and natural resources such as soil and water.

Two sides of the coin

Food waste involves products that are ready to eat but that are not in fact used for human consumption. It is particularly significant in the industrialised countries and is becoming an increasing problem in newly industrialising ones. Food losses, on the other hand, occur between harvest and sale, often in developing countries. The wastage close to home and the losses in the developing country both have a similar effect: they exacerbate food security problems and add unnecessarily to the pressure on the natural factors of production. However, the causes of wastage and loss are very varied and a wide range of stakeholders and institutions are involved: an assortment of political and technical measures is therefore required to tackle the problem. This article looks specifically at plant-based food losses in the developing countries; it should not be forgotten that animal products – meat, fish, milk, eggs – are also affected by losses throughout the value chain, but these have been of less importance in development cooperation projects

Post-harvest protection in development cooperation: the experience of the ’80s and ’90s

As an issue triggered by the severe droughts and famine in the Sahel, post-harvest protection played an important part in German and international development cooperation in the 1980s and ‘90s. During this time BMZ supported several national food security projects involving state storage of food supplies (Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, Niger) and a number of other projects in Africa (Benin, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Tanzania, Togo and Zambia) that included post-harvest protection components. Working with national partner organisations, farmers and field staff, new schemes were devised and disseminated. Various research institutes and universities in the participating countries and in Germany also contributed (among them the Julius Kühn-Institut in Berlin – which was then the Federal Biological Research Centre; see also the article New developments in stored product protection). This work typically involved introducing new techniques and adapting traditional processes in order to improve storage hygiene and prevent infestation. Chemical treatment and fumigation of stored produce were also used if other approaches looked unlikely to succeed.

As well as supporting national crop protection projects, German development cooperation between 1983 and 1998 also supported an integrated Africa-wide campaign against a widespread storage pest, the larger grain borer (Prostephanus truncatus); this was achieved via promotion of a trans-regional project with priority areas in Benin, Ghana, Malawi, Tanzania and Togo. Prostephanus truncatus – an auger beetle of the Bostrichidae family – was brought to Africa from Central America in the late 1970s. Having no natural enemies, it multiplied rapidly and inflicted considerable damage on stored maize and dried manioc. In collaboration with the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) and other international research centres (NRI – Natural Resources Institute, UK; KARI – Kenya Agricultural Research Institute; IIBC – International Institute of Biological Control, UK) the predator Teretriosoma nigrescens was introduced to West Africa from its original home in Central America. It was released first in Togo in 1991 and subsequently in other African countries.

The projects of that period had two main aims. Firstly, they were designed to help the state grain agencies of the Sahel countries provide food in areas in which there were shortages by promoting storage structures, storage management and market information systems. Secondly, they set out to substantially improve the protection of grain, maize, cassava, yams, sweet potatoes and beans stored by village communities and farming families. The specific roles of men and women, especially in connection with the production and post-harvest handling of roots and tubers, were analysed in detail and taken into account in the intervention strategies.

The specific activities included testing different materials and structures for the storage of grain and maize. Exchange visits enabled farmers to learn about different types of storage and hence to identify the type that they would be best advised to build for their own purposes. In some West African countries hundreds of storehouses of different sizes and types were built to provide better medium- and long-term protection for harvested produce that could then serve as a food reserve. In addition, through a range of dialogue and training measures information about better storage and post-harvest management was disseminated and research findings were passed on to multipliers and farmers.

The path to the systemic approach

In the 1990s it was already clear that the ideas put forward were not being accepted everywhere and that the expected success was not materialising (Bell, Mazaud, Mück, 1999). Consideration was therefore extended to socio-economic and socio-cultural conditions; this led to the development of valuable post-harvest protection schemes utilising measures that were widely accepted, feasible and adapted to local conditions. The focus was on the economic viability of the measures and their impact on the producer households’ standard of living. From a nuanced analysis of types of loss it was evident even then that the loss figures quoted in the literature were frequently too high. „The widespread practice of continuous withdrawal of maize from storage for consumption or sale throughout the storage period leads to the actual storage losses being overestimated,“ wrote Bell et al. (1999) based on the fact that the 30 per cent loss in farm maize stores found in Togo after six months therefore corresponded to some 17 per cent of the quantity put into the store (Pantenius 1988).

Building on the concept of integrating protection of stored produce and storage management on the one hand and socio-economic conditions on the other, the system approach to post-harvest activities was developed by the FAO, GTZ and partners in the mid-1990s (on the basis of experience in Ghana, Kenya and Zambia and influenced by the Agenda 21). This was a multi-disciplinary and participative approach that involved all stakeholders at all stages of the “post-harvest chain”. The focus was no longer on pests and technical problems but instead on the people affected by the issues (see “From biological control to a systems approach in the post harvest sector”, IITA / GTZ meeting 1997; Borgemeister et al., 1999). However, the decreasing project activities at that time did not offer much opportunity to implement this concept.

What is now the way forward?

Today the perspective has widened to include the causes of food losses and to consider losses not only at producer level but also along the entire value chain, whether during storage, transport, processing or the various stages of marketing. Measures to reduce loss must therefore take account of the entire value chain and focus on the particular hot spots at which the largest losses occur and the most effective measures can be put in place. This is highly depending on the produce and the regional post-harvest conditions. Planning and implementing loss reduction measures needs to involve many different players in both the public and private sectors. The desired result will not be achieved if storage facilities are built without an adequate transport infrastructure, without market information or without further processing opportunities, and technical innovation without prior cost/benefit analysis, without capacity building and without a sound gender approach is unsustainable. In this regard GIZ will closely cooperate with the “Save Food Initiative” (www.save-food.org), initiated by Messe Düsseldorf and FAO in 2011 (see also the article Who does what in post-harvest loss reduction?). Complex links and interrelationships need to be identified and incorporated into the measures that are devised. For example, this is the case with the analysis of losses, which now needs to include the environmental footprint of production (see also the article Nigeria: how losses in the maize and manioc value chains impact on the environment).

In order not to reinvent the wheel, GIZ has started to connect to main stakeholders in the field of post-harvest protection: in June 2012 it held a seminar entitled “Food losses concern us all” at which key German institutions from research, politics and the private sector exchanged views and planned further collaboration. In July 2012 GIZ and the Global Donor Platform for Rural Development held a “virtual briefing” on post-harvest losses at which the most important international organisations such as the FAO, the World Bank and the African Development Bank and various national institutions such as the Natural Resources Institute (NRI) and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) discussed their measures and strategies for post-harvest losses (www.donorplatform.org/postharvest-losses/virtual-briefings). Other “virtual briefings” are planned. Nowadays GIZ is implementing several projects on rural development and sustainable agriculture together with national partner organisations which integrate post-harvest activities

Food losses – an important topic in GIZ projects

Even if specific post-harvest-management projects, as in the past, do not exist any more, the topic food losses is addressed in many GIZ projects dealing with rural development,

agricultural promotion and especially promotion of agricultural value chains and strengthening resilience of farmers under changing climatic conditions. For the Baghlan Agriculture Project in Afghanistan the development of value chains of wheat, potatoes, fruit and vegetables is a major concern and the project aims that at least 900 enterprises have recorded a significant increase in operating income due to improved storage/processing of market products in Baghlan.

The African Cashew Initiative is a jointly funded programme of BMZ (German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development), Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and private-sector partners, and implemented, amongst others, by GIZ. It addresses food losses in cashew and other value chains and aims for improvements in production and best practices for harvesting and post-harvest handling in all participating countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Mozambique).

The objective of the “Market Oriented Agriculture Programme” (MOAP) in Ghana is to improve the competitiveness of agricultural producers and other agricultural actors in processing, trade and services on national, regional and international markets. Through better market infrastructure at the important wholesale market in Techiman, the quality of maize and the reduction in grain moisture is improved. Furthermore, the exportable share of pineapple is risen nation-wide through improved quality, reduced losses and fruit rejects and improved market access.

In Bolivia, the “Programa de Desarrollo Agropecuario Sustentable” (Sustainable Agricultural Development Programme) aims at improving resilience of smallholder farmers with regard to changing climate conditions. The reduction of post-harvestlosses is one of several options to achieve this goal. The value chains concerned are fruit, vegetable and corn.

Other projects dealing with post-harvest management are in Ethiopia, Laos, Nepal, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Philippines, Usbekistan and Vietnam.

Capacity Development for PHL Reduction

From about 1980 on, German development co-operation (DC) has been strongly involved in disseminating knowhow and experience in warehousing and protecting stored produce. Awareness of problems in protecting stored goods has been sharpened, and state-of-the-art research results have been transmitted; advice has been given to numerous specialists, consultants and producers, and they have been provided with upgrading as well. Alone in Egypt, former GTZ (*) trained more than 1,200 staff of the partner organisations involved in warehouse management and protecting stored produce. In co-operation with GTZ projects and national organisations, the former German Foundation for International Development (DSE) has run regional training courses, especially in Anglophone and Francophone Africa. Regarding grain, the main focus has been on the following topics:

- warehouse hygiene, protecting stored produce, accounting and management of large government grain stocks serving as food security reserves in Sahel countries,

- identifying pests, protecting stored produce, warehouse and other storage structures and handling of grain and maize in small private or community storage buildings.

The accumulated knowhow and experience regarding grain has been recorded in the “Manual on the prevention of post-harvest grain losses” (Gwinner, J., Harnisch, R., Mueck, O., 1996, 334 p.), which is available digitally in English, French and Portuguese.

With regard to cassava, yams, sweet potatoes and other local roots and tubers in sub-Saharan Africa, DSE and its partners organised three specialist conferences between 1989 and 1991, and subsequently ran training measures for multipliers at regional level focusing on harvesting, processing, storage and local marketing. The French-language manual titled “Les richesses du sol” (Bell, A., Mueck, O., Schuler, B., 2000, 237 p.) provides a summary and also covers the topics of gender, participatory training methods and work results of participants.

In 1996, to facilitate international discussion of and access to the most important documents on post-harvest protection, the FAO, working with former GTZ and the Centre de coopération internationale en recherche agronomique pour le développement (CIRAD), set up the internet platform INPhO (the Information Network on Post-harvest Operations), which is still accessible (www.fao.org/inpho). In view of the renewed interest in the issue, GIZ made its most important publications, booklets and reports available to professionals worldwide in digital form at the website of the Global Donor Platform for Rural Development. The above mentioned documents can be seen under “training”:

http://www.donorplatform.org/postharvest-losses/research-library.html

(*) Since 2011, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH covers the competencies and experiences of DED, GTZ und InWEnt. The expertise of DSE was already taken over by InWEnt some years earlier.

Heike Ostermann

heike.ostermann@giz.de

Bruno Schuler

bruno.schuler@giz.de

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH

Eschborn, Bonn, Germany

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment