Download this article in magazine layout

Download this article in magazine layout

- Share this article

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Reconciling trade policies with food security objectives

Agenda 2030 sets out a governance framework, defined by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), that affirms a new vision whereby sustainable development is no longer a question of North–South relationships, but rather a universal concern that involves developed and developing countries alike. It also underscores the importance of taking into account the different national realities, capacities and levels of development, and of respecting national policies and priorities.

At the same time, countries now have a wider range of options for financing their development, with Official Development Assistance (ODA) representing only a small component of these options, and with the pattern of finance (the mix of national, international, public and private sources) evolving at different levels of income and development. This has contributed to a shift in attention from financing towards policy packages designed to create the enabling conditions for the effective mobilisation of different sources of finance appropriate to specific country situations.

Meanwhile, new visions have been taking shape among both donor and beneficiary countries, “inspired” by the principle of economic diplomacy (see Box below), and placing trade at the core of international relations. Donors are increasingly transforming aid relations into trade relations. Developing countries are using trade more and more to promote structural transformation and raise their capacity to use domestic resources to support their own growth and development.

The concept of Economic diplomacy

The developments and the vision of the Agenda 2030 are underpinned by the concept of economic diplomacy, defined as “the process through which countries tackle the outside world, to maximize their national gain in all the fields of activity including trade, investment and other forms of economically beneficial exchanges where they enjoy comparative advantage. It has bilateral, regional and multilateral dimensions, each of which is important” (Rana, 2007). This concept provides the basis for a more holistic approach to international relations that is more concerned with political economy issues, connects national with international policy interests more effectively, views development policies as part of a package of policies, and prioritises long-term transformation over short-term political or commercial interests.

In this transition “beyond aid”, trade policies play an important role in supporting the implementation and financing of agriculture strategies and investment plans. This requires an improved understanding of the links between trade, agriculture and food security, of the role that trade policies can play in creating the enabling conditions for structural transformation, and of the improvements needed in governance and policy-making processes to enable a better balance between national interests and the collective goods provided by the global trade system.

The relationship between trade and food security

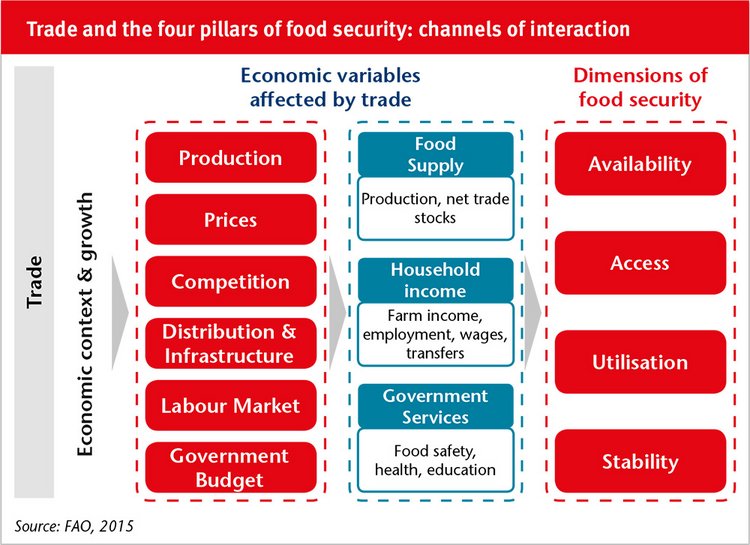

The links between trade and food security are inherently complex. As illustrated in the Figure on page 14, trade impacts all the four dimensions of food security by inducing changes in a number of economic and social variables. These impacts can be positive or negative and can evolve over time, possibly working in different directions in the short and long term. They are also influenced by the economic context and other domestic factors such as the functioning of markets, the responsiveness of producers to changing incentives and the geographical distribution of food insecurity.

The complexity of these interactions explains why the trade effects on food security are very mixed and context-specific, as empirical evidence also confirms. For example, McCorriston et al. (2013), after reviewing 34 studies on the effects of trade reforms and food security, conclude that 13 studies reported improvements in the food security indicators used, ten showed declines, and the other eleven had mixed results, “with food security metrics varying across segments of the population, regions and periods, or with alternative food security metrics indicating different outcomes for specific countries”.

Therefore, “trade is neither an inherent threat to, nor a panacea for improved food security, but it poses challenges and risks that need to be considered in policy decision making.” (FAO, 2015)

Long-term considerations need more attention

The challenges in generalising a relationship between trade and food security make it difficult to identify a single most “appropriate” policy instrument. The appropriateness of a trade policy is rather linked to the objectives of policy interventions, with particular attention to short- and long-term objectives. The same policy instrument can have quite different results in terms of food security under different circumstances.

The debate about trade and food security has tended to focus mainly on short-term policy interventions in response to market shocks, and on analysing and managing the resulting short-term consequences in terms of changes in trade flows and prices for consumers and producers.

When positioning the policy debate in a longer-term perspective, and considering the dynamics of structural transformation that are common to the development pathways of most countries, the determinants of trade policies supportive of improved food security change significantly.

In this perspective, the appropriateness of trade policies is determined by the stage of development of the specific country, and by the role of the agriculture sector within that country’s economy. In countries in early stages of development, the provision of public goods such as market infrastructure and research and development may be paramount. As markets develop, a more interventionist approach to reduce production risks and provide incentives for productivity improvements may be required. As development proceeds and the agricultural sector becomes less important in its share of the economy, progressive withdrawal from market activities and a more liberal agricultural trade policy to allow the private sector to play an increasingly active role will be needed (Dorward and Morrison, 2000).

“Taking this longer-term perspective, the question is not whether, but when and how countries should open their agriculture sectors to greater competition.” (FAO, 2015)

Trade policy responses to the food price crises and their short- and long-term impacts

In 2007–2008, in response to the rise in food prices and to increased price volatility, a number of countries put in place export restrictions (net exporting countries), or reduced import barriers (net importing countries), to stabilise supplies on domestic markets. While these policies helped to achieve the short-term national objectives of increasing food availability and lowering food prices, in the medium and long term, their negative impacts at both national level (disincentives for farmers created by an uncertain policy environment) and global level (upward pressure exerted on world prices by a tightening of the balance between demand and supply, and exacerbation of uncertainty and volatility in food markets) have become visible. The negative impacts in the long term can significantly undermine any short-term gains.

Improved governance for trade and food security

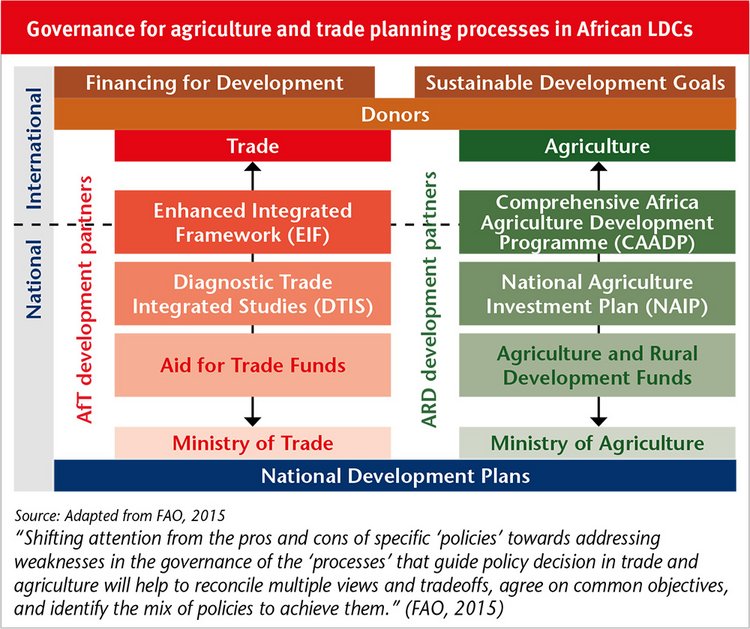

In addition to prioritising short-term policy considerations over long-term ones, the debate on trade and food security has also been dominated by discussions on the pros and cons of different policies, and on the “policy space”, or flexibilities, provided under trade agreements. This has resulted in polarised positions, making it difficult to find the right balance between ensuring that countries are not restricted in their use of policies to pursue their national food security concerns, and that, at the same time, they “do no harm” to third countries. Less attention has been given to the policy-making “processes” (the interactions and competing forces that shape policy decisions). A closer look at such processes suggests major challenges in cross-sectoral co-ordination. In most developing countries, trade and food security objectives are identified through separate prioritisation, negotiation and co-ordination processes, associated with different ministries (trade and agriculture) and involving different stakeholders, development partners and sources of financial support. This has resulted in weak strategies and has reduced the capacity of developing countries to take advantage of market opportunities. The example of least-developed countries in Africa, where processes supporting agriculture and trade development are quite separate, is emblematic.

Conclusions

Debates on the appropriate use of trade policy in support of food security have tended to focus on the short-term economic costs and benefits to economies, but have neglected both their longer-term impacts and the complex processes through which approaches to developments in the realms of trade, agricultural and food security are determined. A more pragmatic approach focused on the specificity of the country context will help to ensure greater coherence between trade policies, agriculture sector development, and the food security priorities of different countries. Focusing on policy-making processes rather than on the pros and cons of different policies will help to balance competing objectives and improve policy coherence.

To assist countries in achieving greater coherence between trade policies and food security objectives, the international community should increase its efforts to support developing countries in strengthening their capacities to analyse the implications of trade and related policies for achieving longer-term food security objectives; in facilitating policy dialogue to improve alignment and coherence between agricultural development strategies and trade-related policy frameworks; and in better engaging in the regional and global trade-related processes that shape international trade agreements, to ensure that they are coherent with and supportive of the achievement of food security in all countries.

Eleonora Canigiani, Jamie Morrison &

Ekaterina Krivonos

UN Food and Agriculture Organization

(FAO) Rome, Italy

Contact: Eleonora.Canigiani@fao.org

References and further reading

- S. McCorriston, D.J. Hemming, J.D. Lamontagne-Godwin, J. Osborn, M.J. Parr and P.D. Roberts (2013). What is the evidence of the impact of agricultural trade liberalization on food security in developing countries? A systematic review. London, EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London. http://www.cabi.org/Uploads/CABI/about-us/Scientists%20output/Agri-liberalisation-systematic-review.pdf

- K. Rana (2007). Economic diplomacy: the experience of developing countries. In N. Bayne and S. Woolcock, eds. The new economic diplomacy: decision making and negotiations in international relations, pp. 201–20. London, Ashgate. Publishing Limited.

- A. Dorward and J. Morrison (2001). The agricultural development experience of the past 30 years: lessons for LDCs. Imperial College London. Paper prepared for FAO.

- FAO (2006). Trade Policy technical Notes No. 14. Towards appropriate agricultural trade policy for low income developing countries. ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/009/j7724e/j7724e00.pdf

- FAO (2015). The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2015-16. Trade and food security: achieving a better balance between national priorities and the collective good. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5090e.pdf

Add a comment

Be the First to Comment